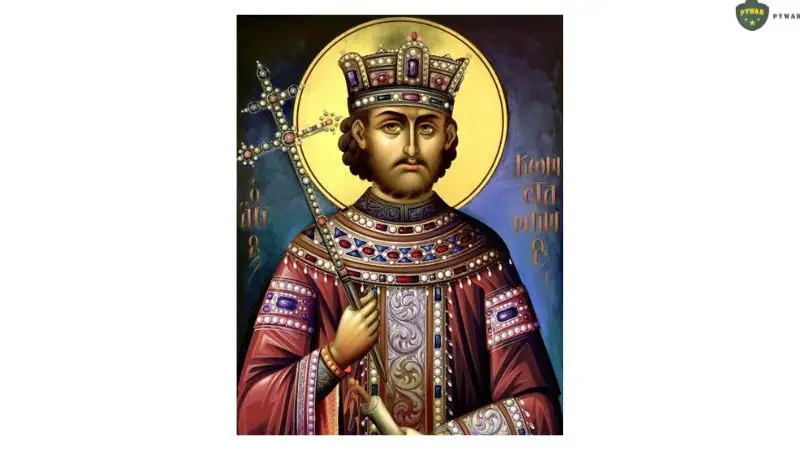

Constantine the Great, also known as Constantine I, Emperor Constantine, or the First Christian Emperor, stands as one of the most transformative figures in Roman history. His reign marked the Christianization of Rome, reshaping the Roman Empire through his conversion to Christianity, the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, and the Edict of Milan. From his early life to his establishment of Constantinople and contributions to Early Christianity, Constantine’s legacy endures as a cornerstone of the Byzantine Empire foundations. This article explores his life, childhood, career, death, and lasting impact, weaving in key elements of Roman political history, Roman military strategy, and Roman religious reform.

Who Was Constantine the Great?

Constantine I (c. 272–337 AD) was a Roman Emperor who ruled from 306 to 337 AD, celebrated as the Constantine the Victor for his military triumphs and the Founder of Constantinople for establishing the new imperial capital. Born in Naissus (modern Niš, Serbia), he rose to power during the Tetrarchy, a system of divided rule, and became the sole ruler of the Roman Empire by 324 AD.

His most enduring contribution was his role as the First Christian Emperor, promoting Christianity through landmark actions like the Edict of Milan and the Council of Nicaea, which shaped the Nicene Creed. Guided by a divine vision of the Chi Rho symbol, Constantine’s embrace of Roman Christianity transformed the empire’s religious landscape, earning him veneration as Saint Constantine in some Christian traditions.

Childhood of Constantine the Great

Constantine I was born around February 27, 272 AD, in Naissus, in the Roman province of Moesia Superior (modern Serbia). His father, Flavius Constantius (later Constantius Chlorus), was a military officer of Illyrian descent who rose to become a Caesar in the Tetrarchy. His mother, Helena (later Saint Helena), was of humble origins, possibly a tavern worker, and a devout Christian who influenced Constantine’s later faith. Growing up in a military family, Constantine’s childhood was shaped by the turbulent Roman political history of the late 3rd century, marked by civil wars and Diocletian’s reforms.

As a youth, Constantine was sent to the court of Emperor Diocletian in Nicomedia (modern İzmit, Turkey) around 285 AD, serving as a hostage to ensure his father’s loyalty. There, he received a formal education in Latin, Greek, philosophy, and military tactics, immersing him in the administrative and cultural life of the Roman Empire. He also witnessed Diocletian’s Great Persecution of Christians (303–313 AD), which contrasted with his mother’s Christian beliefs. His time in Nicomedia exposed him to the complexities of the Tetrarchy, preparing him for his future role. In 305 AD, when Diocletian and Maximian abdicated, Constantine joined his father in Gaul, campaigning in Britain, where he honed his skills in Roman military strategy.

Career Path of Constantine the Great

Constantine’s career was a remarkable ascent from soldier to sole emperor, defined by Constantine’s military campaigns, political maneuvering, and Roman religious reform. His path unfolded as follows:

Rise to Power (306–312 AD)

In 305 AD, Constantius Chlorus became Augustus of the West, and Constantine joined him in Britain. Upon his father’s death in 306 AD in Eboracum (York), Constantine’s troops proclaimed him Augustus, bypassing the Tetrarchy’s succession rules. Facing rivals like Maxentius, who controlled Rome, and Galerius, who initially denied his title, Constantine consolidated power in Gaul and Britain, strengthening his legions and fortifying the Rhine frontier.

His defining moment came during the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (October 28, 312 AD). Marching along the Via Flaminia to confront Maxentius, Constantine reportedly experienced a divine vision of the Chi Rho symbol with the words “In hoc signo vinces” (“In this sign, you shall conquer”). Adopting the Labarum standard and painting the Chi Rho on his soldiers’ shields, Constantine defeated Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge over the Tiber River. Maxentius drowned in the Tiber River in history, and Constantine entered Rome (city) in triumph, disbanding the Praetorian Guard and erecting the Arch of Constantine to commemorate his victory. This Battle of 312 marked his Christian conversion and solidified his control over the Western Empire.

Consolidation and Unification (313–324 AD)

In 313 AD, Constantine and co-emperor Licinius issued the Edict of Milan, granting tolerance to Christianity and restoring confiscated church properties. This marked a turning point in the Christianization of Rome, ending the persecution of Christians. Constantine’s support for Early Christianity included funding church construction, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, inspired by Helena’s pilgrimages.

However, tensions within the Tetrarchy persisted. By 316 AD, Constantine clashed with Licinius, who ruled the Eastern Empire. After a series of campaigns, including victories at Cibalae (316 AD) and Adrianople (324 AD), Constantine defeated Licinius in 324 AD at the Battle of Chrysopolis, achieving the unification of the Roman Empire under his sole rule. His Roman military history showcased disciplined legions, innovative tactics, and strategic use of cavalry.

Founding Constantinople and Religious Reforms (324–337 AD)

In 324 AD, Constantine founded Constantinople (modern Istanbul) on the site of Byzantium, establishing it as the new capital of the Roman Empire in 330 AD. This act laid the Byzantine Empire foundations, shifting the empire’s center eastward. Constantinople’s strategic location enhanced trade and defense, reflecting Constantine’s vision for a Christian empire.

Constantine’s Constantine and Christianity legacy includes convening the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, which addressed the Arian controversy and produced the Nicene Creed, a cornerstone of Christian doctrine. He promoted Roman religious reform by granting privileges to Christian clergy, banning pagan sacrifices, and standardizing Christian practices, though he tolerated paganism to maintain stability. His Labarum standard became a symbol of Christian military might.

Later Reign and Legacy

Constantine’s later years focused on consolidating power, reforming the Roman administration, and strengthening the military. He reorganized the Roman army, creating mobile field units (comitatenses) and reducing reliance on static border garrisons. His campaigns against the Goths and Sarmatians along the Danube secured the empire’s frontiers. By his death, Constantine had transformed the Roman Empire into a Christian-oriented state, leaving a lasting Constantine’s legacy in both governance and religion.

Why Did Constantine the Great Die?

Constantine I died on May 22, 337 AD, in Nicomedia, shortly after a planned campaign against the Sassanid Empire. Historical sources, including Eusebius, indicate that Constantine fell ill in early 337 AD, possibly from a fever or poisoning, though the exact cause remains uncertain. He traveled to the hot springs of Helenopolis (named after his mother, Helena) seeking relief, but his condition worsened. On his deathbed, Constantine was baptized by Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, a significant act for the First Christian Emperor, as he had delayed baptism until near death, a common practice to ensure forgiveness of sins.

His death at age 65 marked the end of a transformative reign. Constantine’s body was taken to Constantinople, where he was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles, surrounded by relics of the apostles, symbolizing his role as the Augustus Constantine who bridged the Roman and Christian worlds. His sons—Constantine II, Constans, and Constantius II—divided the empire, leading to renewed instability.

Conclusion

Constantine the Great, born in 272 AD in Naissus, rose from a military upbringing to become the First Christian Emperor, forever altering the Roman Empire through his Christian conversion and Constantine’s military campaigns. His childhood in Diocletian’s court and early campaigns shaped his mastery of Roman military strategy, culminating in the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 AD, where the Chi Rho symbol inspired his victory over Maxentius. The Edict of Milan, Council of Nicaea, and founding of Constantinople cemented his role in the Christianization of Rome and the Byzantine Empire foundations.

Despite his death in 337 AD from illness, Constantine’s legacy endures through the Arch of Constantine, the Nicene Creed, and the spread of Christianity across the empire. For historians and enthusiasts, Constantine of Rome remains a towering figure whose vision and reforms reshaped Roman political history and Roman religious history, making him a pivotal architect of the Western world’s religious and cultural evolution.