The Battle of Raphia, fought on June 22, 217 BC, stands as one of the most significant ancient battles in military history, marking a critical moment in the Hellenistic period. This monumental clash between the Ptolemaic Kingdom under Ptolemy IV Philopator and the Seleucid Empire led by Antiochus III the Great during the Fourth Syrian War determined the fate of Coele-Syria, a vital region in the Mediterranean conflicts. Known for its massive scale and the rare confrontation of African and Indian war elephants, the battle showcased Hellenistic warfare and ancient military tactics at their peak.

This article delves into the time, location, causes, detailed course, casualties, and outcome of the Battle of Raphia, highlighting its role in the Ptolemaic-Seleucid rivalry and its lasting impact on the Hellenistic kingdoms.

Time and Date of the Battle

The Battle of Raphia occurred on June 22, 217 BC, during the Fourth Syrian War (219–217 BC), a conflict rooted in the ongoing Syrian Wars between the Ptolemaic Kingdom and the Seleucid Empire. This date marked the culmination of a two-year campaign as both Hellenistic kings, Ptolemy IV Philopator and Antiochus III the Great, sought to assert dominance over Coele-Syria, a strategically critical region encompassing modern-day Syria, Lebanon, and parts of Israel.

Location of the Battle

The battle was fought near the town of Raphia, located in present-day Rafah, close to Gaza in the northeastern corner of modern Egypt, near the border with Coele-Syria. Situated approximately five miles southwest of Gaza, the battlefield was strategically chosen, with dunes providing natural protection for the Ptolemaic army’s flanks against the Seleucid military’s superior cavalry. The proximity to the Mediterranean coast and the Jiradi Pass made Raphia a key point in controlling trade and military routes, amplifying its significance in Mediterranean conflicts.

Causes of the Conflict

The Battle of Raphia was a direct result of the Ptolemaic-Seleucid rivalry over Coele-Syria, a fertile and strategically vital region that served as a gateway to Egypt and a hub for trade routes. The Syrian Wars, a series of six conflicts between the Ptolemaic Kingdom and the Seleucid Empire, were driven by the ambition to control this contested territory, which had been a point of contention since the division of Alexander the Great’s empire.

The Fourth Syrian War began in 219 BC when Antiochus III the Great, seeking to restore Seleucid Empire territories lost in earlier wars, launched an invasion of Coele-Syria. His campaign was bolstered by the defection of Theodotus the Aetolian, a former Ptolemaic general who handed over key cities like Tyre and Ptolemais to the Seleucids.

Ptolemy IV Philopator, ruling a Ptolemaic Kingdom weakened by court intrigue and the murder of his mother, Berenice II, faced significant pressure to respond. His chief minister, Sosibius, orchestrated a massive recruitment effort, including 20,000–30,000 native Egyptians trained as phalangites, a departure from the traditional reliance on Greek mercenaries. This move addressed manpower shortages but sowed seeds of future unrest. Antiochus’s prolonged consolidation in Phoenicia gave Ptolemy time to prepare, leading to the inevitable clash at Raphia to determine control over Coele-Syria.

Course of the Battle

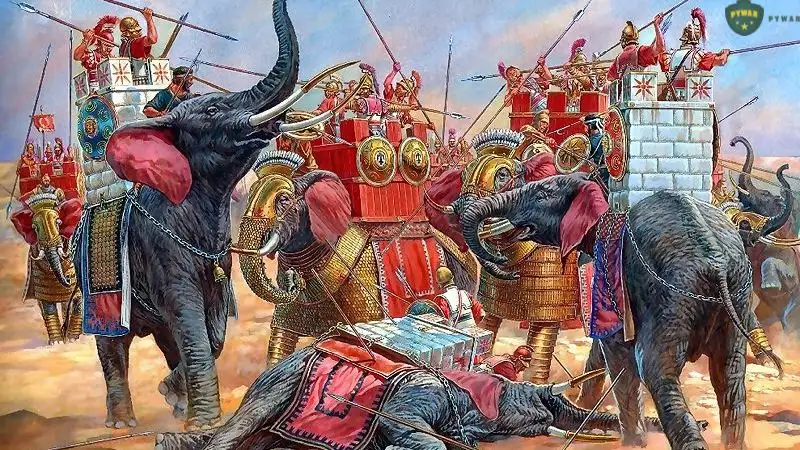

The Battle of Raphia was a masterclass in Hellenistic warfare, characterized by ancient battle formations, intricate battle tactics, and the dramatic use of war elephants. Both armies, totaling between 120,000 and 150,000 men, were among the largest of the ancient battles, rivaling the scale of the Battle of Ipsus (301 BC). According to historian Polybius, Ptolemy IV commanded approximately 70,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 73 war elephants (likely North African bush elephants), while Antiochus III led 62,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 102 Indian war elephants.

Pre-Battle Maneuvers

In the spring of 217 BC, Ptolemy IV mobilized his army from Alexandria, crossing the Sinai Desert at a pace of 22 miles per day to reach Raphia. Antiochus III responded by moving his forces south from Gaza, setting up camp initially 10 stades (about 2 km) from the Ptolemaic camp, later closing to 5 stades (1 km). This proximity led to five days of skirmishing, including a failed assassination attempt by Theodotus the Aetolian on Ptolemy’s life. On June 17, both kings decided to engage in full battle, deploying their forces in traditional Hellenistic warfare formations.

Army Composition and Deployment

Both armies followed standard ancient military tactics, placing their Macedonian-style phalanxes—heavily armed infantry wielding long sarissa pikes—at the center. Flanking the phalanxes were light infantry and mercenaries, with cavalry on the wings and war elephants positioned in front. Ptolemy IV stationed himself on his left wing, facing Antiochus III on the Seleucid right, each commanding their elite units. The Ptolemaic army included 20,000 native Egyptian phalangites, a significant innovation, alongside Greek mercenaries, Thracians, and Gauls. The Seleucid military boasted 10,000 elite Argyraspides (Silver Shields), 10,000 Arabians under Zabdibelus, and diverse contingents from Medes, Persians, and Cretans.

The Battle Unfolds

The battle began with a dramatic charge of the war elephants, a hallmark of war elephant strategy. Ptolemy’s African elephants, likely smaller North African bush elephants (Loxodonta africana), panicked at the sight and smell of Antiochus’s larger Indian elephants (Elephas maximus), retreating and disrupting Ptolemaic infantry lines. This gave the Seleucids an early advantage on the flanks. Simultaneously, Antiochus III led his right-wing cavalry, outflanking Ptolemy’s left-wing elephants and routing the Ptolemaic cavalry. However, Ptolemy slipped from his left wing to the center, rallying his phalanx.

On the Ptolemaic right, the cavalry, supported by the terrain’s dunes, held firm against the Seleucid left, preventing a complete encirclement. The central phalanxes clashed in a grueling contest, with the Ptolemaic army’s native Egyptian phalangites proving decisive. Their discipline and training, combined with Ptolemy’s leadership, broke the Seleucid phalanx, which began to retreat. Antiochus, still pursuing the Ptolemaic left, was unaware of the collapse in his center until dust clouds signaled his army’s rout. Unable to regroup, as most of his men fled to Raphia, Antiochus retreated to Gaza.

Key Turning Points

The Ptolemaic army’s success hinged on the resilience of its phalanx and the strategic use of terrain to neutralize the Seleucid military’s cavalry advantage. The failure of Ptolemy’s war elephants was offset by the unexpected strength of the native Egyptian troops, whose performance marked a shift in ancient Egyptian warfare. Antiochus’s overconfidence in his cavalry and elephant superiority, coupled with his detachment from the central phalanx, led to his defeat.

Casualties

According to Polybius, the Seleucid Empire suffered heavy losses: approximately 10,000 infantry, 300 cavalry, and 5 elephants killed, with 4,000 men taken prisoner. The Ptolemaic Kingdom lost 1,500 infantry, 700 cavalry, and 16 elephants, with most of their surviving elephants captured by the Seleucids. These figures reflect the intensity of the phalanx clash and the chaotic rout of the Seleucid forces, where most casualties occurred during the flight. The disparity in losses underscores the decisive nature of Ptolemy’s victory, despite the failure of his war elephant strategy.

Who Won the Battle of Raphia?

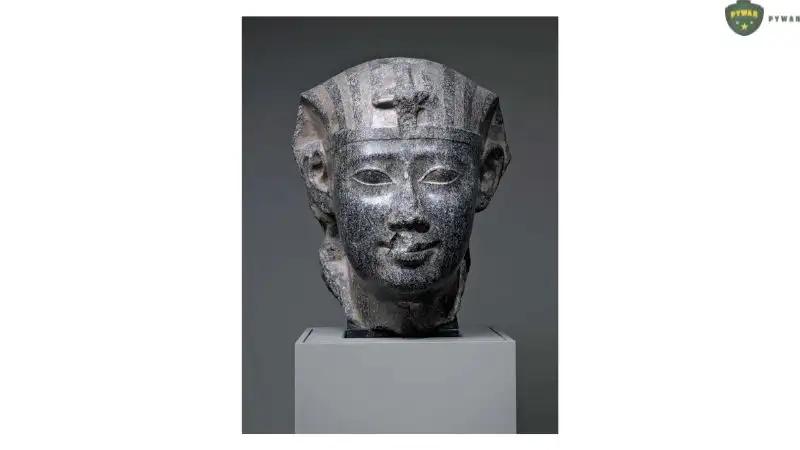

Ptolemy IV Philopator emerged victorious at the Battle of Raphia, securing Coele-Syria for the Ptolemaic Kingdom. Following the battle, Antiochus III requested a truce to bury his dead, which Ptolemy granted, before retreating to Antioch. The victory reaffirmed Ptolemaic control over Coele-Syria and Phoenicia, strengthening Ptolemy’s rule. However, the triumph was temporary; in 200 BC, Antiochus defeated Ptolemy V Epiphanes at the Battle of Panium, reclaiming Coele-Syria and Judea. The Raphia Decree, inscribed in Greek, hieroglyphic, and demotic Egyptian, celebrated Ptolemy’s victory and marked the first time a Ptolemaic king received full pharaonic honors in both Greek and Egyptian texts, reflecting the growing influence of native Egyptians.

Conclusion

The Battle of Raphia, fought on June 22, 217 BC, near modern Rafah, was a defining moment in Hellenistic warfare and military history. Driven by the Ptolemaic-Seleucid rivalry over Coele-Syria, the battle showcased ancient military tactics, from phalanx formations to the dramatic but flawed war elephant strategy. Ptolemy IV Philopator’s victory, bolstered by the innovative inclusion of native Egyptian phalangites, secured Coele-Syria for the Ptolemaic Kingdom, but the high cost of the Fourth Syrian War and the empowerment of Egyptian troops sowed seeds of future unrest, including the Egyptian Revolt (207–186 BC).

Antiochus III the Great’s defeat marked a temporary setback, but his later successes highlighted the ongoing volatility of the Syrian Wars. The Battle of Raphia remains a testament to the complexity of ancient battles, the strategic brilliance of Hellenistic kings, and the enduring legacy of Mediterranean conflicts in shaping the Hellenistic kingdoms.

Sources:

- Polybius

- The Histories

- Book 5

- Bar-Kochva

- The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns

- Bevan

- A History of Egypt Under the Ptolemaic Dynasty

- Grainger

- The Seleukid Empire of Antiochus III (223–187 BC)