In the annals of ancient Greece, the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC stands as a turning point in history, where the Greek city-states, united under the Hellenic League, defied the mighty Persian Empire. Through masterful naval tactics and Greek unity, the Greek Navy, led by Themistocles, shattered the Persian Navy’s ambitions, securing Greek independence during the Greco-Persian Wars. This article delves into the battle’s timing, location, progression, casualties, outcome, and enduring legacy, immersing readers in the drama of naval warfare that shaped Classical Greek history.

When Did the Battle of Salamis Take Place? Where?

The Battle of Salamis occurred in September 480 BC, during the Second Persian War, a critical phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. It took place in the narrow straits between Salamis Island and the mainland of Attica, near Athens, in the Aegean Sea. The battle followed the Persian invasion led by Xerxes I, who sought to conquer the Greek city-states after the heroic stand at the Battle of Thermopylae. The Hellenic League, comprising Athens, Sparta, Corinth, and others, rallied to resist the Persian Army and Persian Navy.

The straits of Salamis Island, with their confined waters and rocky shores, offered a strategic advantage for the Greek Navy’s trireme ships, designed for agility in battle in narrow straits. This location, chosen by Themistocles, proved pivotal in countering the numerical superiority of the Persian fleet, setting the stage for a Greek victory that altered European history.

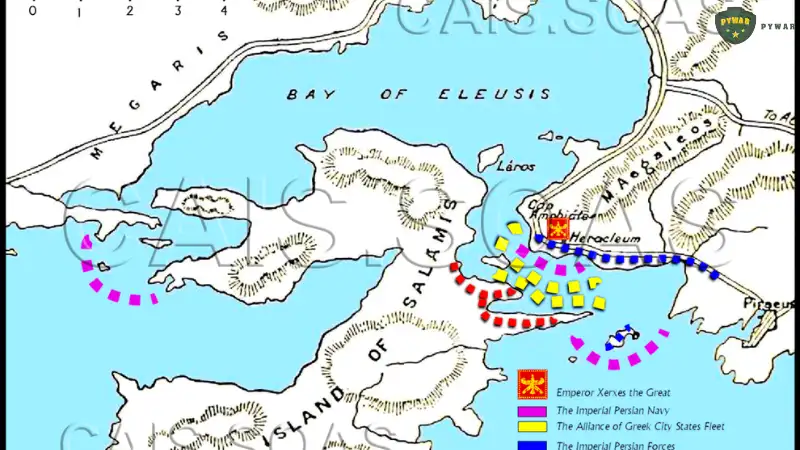

Map of the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis unfolded in the narrow straits between Salamis Island and the Attica mainland, with Psyttaleia Island at the center of the channel. The Aegean Sea’s coastal geography shaped the battle’s dynamics, favoring the Greek Navy’s maneuverability over the Persian Navy’s larger fleet. The battlefield can be visualized as follows:

- Greek positions: The Greek Navy, numbering around 370 trireme ships, was positioned in the straits, with Themistocles commanding the Athenian navy, Eurybiades of Sparta leading the fleet, and the Aeginetan fleet providing support. The triremes were anchored near Salamis Island’s eastern shore.

- Persian positions: The Persian Navy, with 600–1,200 ships under Xerxes I, assembled in the open waters of the Aegean Sea, stretching from Psyttaleia Island to the mainland. Artemisia I of Caria, a Persian ally, commanded a contingent.

- Terrain features: The narrow straits restricted the Persian fleet’s movements, while Psyttaleia Island served as a focal point for Persian infantry deployment.

Themistocles’ strategic deception, including a false message to lure the Persians into the straits, leveraged the terrain to maximize Greek naval power, setting the stage for naval supremacy.

Main Developments of the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis was a masterclass in naval strategy, with Themistocles’ Athenian leadership turning the tide against Xerxes I’s Persian invasion of Greece. The battle’s progression, marked by cunning naval tactics and fierce maritime warfare, unfolded in three dramatic phases, each a testament to Greek resistance and the Hellenic League’s resolve.

Prelude and Strategic Deception

In the days before the battle, the Greek city-states faced internal discord. Eurybiades, the Spartan commander, hesitated to engage the larger Persian Navy, favoring retreat. Themistocles, however, insisted on fighting in the battle in narrow straits, where the Greeks’ trireme ships could outmaneuver the Persians. To force the issue, Themistocles employed strategic deception, sending a trusted slave, Sicinnus, to Xerxes I with a false message claiming the Greeks were retreating. Convinced of an easy victory, Xerxes I ordered his fleet into the straits, falling into Themistocles’ tactics.

On the eve of battle, the Greek Navy, including the Athenian navy and Aeginetan fleet, prepared their triremes, while Artemisia I of Caria advised caution to Xerxes I, to no avail. The Persian Navy positioned itself overnight, exhausting its rowers, while the Greeks rested, ready for maritime warfare.

Opening Clash (Morning)

At dawn in September 480 BC, the Persian Navy sailed into the straits, their ships packed tightly in the confined waters. The Greek Navy, anchored off Salamis Island, sprang into action. Themistocles’ naval tactics emphasized ramming and boarding, with Greek triremes using their bronze rams to puncture Persian hulls. The Athenian navy, forming the core of the fleet, struck first, targeting the Persian vanguard. Corinth’s ships supported the center, while the Aeginetan fleet outflanked stragglers.

The Persian fleet, hampered by the narrow straits, struggled to maneuver. Artemisia I of Caria’s contingent fought fiercely, but the chaotic Persian formation led to collisions and disarray. Xerxes I, watching from a throne on the Attica shore, saw his fleet falter as the Greek naval power asserted dominance.

Decisive Engagement and Persian Collapse

As the battle intensified, the Greek triremes exploited their agility, ramming and sinking Persian ships in rapid succession. The Hellenic League’s cohesion, bolstered by Spartan contribution and Athenian leadership, overwhelmed the Persian Navy. A key moment came when the Greeks lured a Persian detachment toward Psyttaleia Island, where Greek hoplites slaughtered the stranded Persian infantry.

The Persian defeat became inevitable as their fleet, unable to retreat effectively, suffered heavy losses. Artemisia I of Caria escaped, but most Persian ships were destroyed or captured. By midday, the Greek victory was clear, with the straits littered with wreckage. The Persian Navy’s collapse marked a turning point in history, forcing Xerxes I to reconsider his Persian invasion.

Aftermath and Pursuit

The Greeks pursued the retreating Persian fleet, ensuring no counterattack. Xerxes I, shaken by the defeat, withdrew much of his Persian Army from Greece, leaving a smaller force under Mardonius to continue the campaign. The Greek Alliance, emboldened by naval supremacy, prepared for the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC, cementing their Greek independence.

Casualties of the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis exacted a heavy toll, reflecting the ferocity of ancient naval battles:

- Greek Navy: The Hellenic League lost approximately 40–50 trireme ships, with estimates of 1,000–2,000 casualties among rowers and marines. The Athenian navy and Aeginetan fleet bore the brunt, but losses were minimal compared to the Persians.

- Persian Navy: The Persian defeat was catastrophic, with 200–300 ships sunk or captured, and tens of thousands of sailors and soldiers killed, including those on Psyttaleia Island. The loss of ships crippled Xerxes I’s maritime power.

These figures, drawn from ancient sources like Herodotus, underscore the Greek victory’s scale and the Persian Empire’s devastation, reinforcing Salamis’s role in Classical Greek history.

Who Won the Battle of Salamis?

The Battle of Salamis resulted in a decisive Greek victory, with the Hellenic League, led by Themistocles and Eurybiades, defeating the Persian Navy under Xerxes I. The Athenian navy’s naval tactics and the Greek triremes’ agility outmatched the larger Persian fleet, securing Greek independence. The victory, following the Battle of Thermopylae, halted the Persian invasion of Greece and set the stage for the Battle of Plataea.

The Greek Alliance’s triumph strengthened Athenian democracy and elevated Athens as a maritime power, while Sparta and Corinth’s contributions solidified the Hellenic League. The Persian retreat marked a turning point, weakening Xerxes I’s empire and ensuring post-Salamis Greece’s resilience.

Conclusion

The Battle of Salamis in 480 BC was a triumph of Greek naval power and Themistocles’ tactics, forever altering the Greco-Persian Wars. In the narrow straits of Salamis Island, the Greek Alliance’s trireme ships crushed the Persian Navy, securing Greek independence and shaping Classical Greek history. Themistocles’ strategic deception, Athenian leadership, and Spartan contribution turned the tide against Xerxes I, marking a turning point in history. The legacy of Salamis endures in ancient naval battles, a testament to Greek unity and naval supremacy that safeguarded European history.