The Fourth Syrian War (219–217 BC) stands as a pivotal chapter in Hellenistic conflicts, epitomizing the fierce Ptolemaic-Seleucid rivalry over Coele-Syria. This ancient warfare struggle between Ptolemy IV Philopator of the Ptolemaic Kingdom and Antiochus III the Great of the Seleucid Empire culminated in the Battle of Raphia, a monumental clash showcasing war elephants and intricate battle tactics. The war, part of the broader Syrian Wars, reshaped Mediterranean history by determining control over a vital region. This article explores the time, location, causes, course, casualties, and outcome of the Fourth Syrian War, highlighting its significance in Hellenistic kingdoms and ancient territorial conflicts.

Time and Date of the Battle

The Fourth Syrian War spanned from 219 to 217 BC, with its decisive engagement, the Battle of Raphia, fought on June 22, 217 BC. This date, documented by historian Polybius in The Histories, marked the climax of a two-year campaign as Ptolemy IV Philopator and Antiochus III the Great vied for dominance in Coele-Syria. The war’s timeline reflects the prolonged military campaigns and ancient diplomacy that preceded the battle, as both sides maneuvered to secure strategic advantages in the Hellenistic warfare theater.

Location of the Battle

The Battle of Raphia, the war’s defining moment, took place near Raphia, a town in modern-day Rafah, near Gaza in the northeastern corner of present-day Egypt, close to the border with Coele-Syria. Located approximately five miles southwest of Gaza, the battlefield featured open plains flanked by dunes, which provided natural protection for the Ptolemaic army’s flanks against the Seleucid Empire’s superior cavalry. The region’s proximity to the Mediterranean coast and the Jiradi Pass made Raphia a critical chokepoint for controlling trade and military routes in Mediterranean power struggles. The broader campaign unfolded across Coele-Syria, encompassing modern Syria, Lebanon, and parts of Israel, with key cities like Tyre and Ptolemais changing hands before the final clash.

Causes of the Conflict

The Fourth Syrian War was driven by the enduring Ptolemaic-Seleucid rivalry over Coele-Syria, a fertile and strategically vital region central to the Syrian Wars. The Hellenistic kingdoms, formed after Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BC, competed fiercely for territorial dominance, with Coele-Syria serving as a buffer zone and economic hub. Several factors precipitated the conflict:

- Antiochus III’s Ambitions: Antiochus III the Great, ascending to the Seleucid throne in 223 BC, sought to restore the Seleucid Empire’s lost territories. His early successes against the Parthians and Bactrians emboldened him to challenge the Ptolemaic Kingdom for Coele-Syria, which had been under Ptolemaic control since the Third Syrian War (246–241 BC).

- Ptolemaic Weakness: Ptolemy IV Philopator, ruling from 221 BC, inherited a kingdom weakened by internal strife, including the murder of his mother, Berenice II, and court intrigues led by his minister Sosibius. This instability made Coele-Syria vulnerable to Seleucid aggression.

- Theodotus’s Defection: In 219 BC, Theodotus the Aetolian, a Ptolemaic governor, defected to Antiochus III, handing over key cities like Tyre and Ptolemais. This betrayal gave Antiochus a foothold in Coele-Syria, prompting the Fourth Syrian War.

- Strategic and Economic Stakes: Coele-Syria’s control offered access to trade routes, tax revenues, and military staging grounds. Both Hellenistic rulers recognized its importance, making the region a focal point of ancient territorial conflicts.

- Diplomatic Failures: Efforts at ancient diplomacy, including negotiations mediated by neutral parties like Rhodes, failed to resolve the dispute, as Antiochus’s aggressive campaign and Ptolemy’s determination to retain Coele-Syria set the stage for war.

These factors fueled the Syrian campaign history, leading to a confrontation that would test the ancient military strategy of both empires.

Course of the Battle

The Fourth Syrian War culminated in the Battle of Raphia, a showcase of Hellenistic warfare and ancient battle formations. The war’s broader campaign saw Antiochus III capture Seleucia-in-Pieria in 219 BC and advance through Coele-Syria, seizing cities like Tyre and Ptolemais. Ptolemy IV, under Sosibius’s guidance, spent 218 BC reorganizing his Egyptian army, recruiting 20,000–30,000 native Egyptians as phalangites—a bold departure from reliance on Greek mercenaries. By spring 217 BC, both armies converged at Raphia for the decisive battle.

Pre-Battle Maneuvers

Ptolemy IV marched from Alexandria across the Sinai Desert at 22 miles per day, establishing a camp near Raphia. Antiochus III moved south from Gaza, positioning his army initially 10 stades (2 km) from Ptolemy’s camp, later closing to 5 stades (1 km). Five days of skirmishing followed, including a failed assassination attempt by Theodotus on Ptolemy. On June 17, both kings opted for a pitched battle, deploying massive armies: Ptolemy with 70,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 73 African war elephants, and Antiochus with 62,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 102 Indian war elephants.

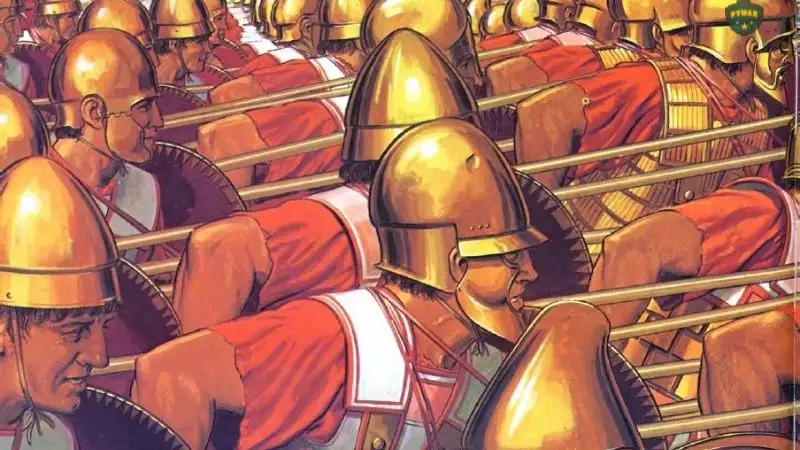

Army Deployment

Both sides employed ancient military strategy, centering their armies on Macedonian-style phalanxes armed with sarissa pikes. The Ptolemaic army included 20,000 native Egyptian phalangites, Greek mercenaries, Thracians, and Gauls, with cavalry and war elephants on the wings. Antiochus III’s Seleucid military featured 10,000 elite Argyraspides, 10,000 Arabians under Zabdibelus, and diverse contingents from Medes, Persians, and Cretans. Ptolemy commanded his left wing, facing Antiochus on the Seleucid right, each leading elite units.

The Battle

The battle began with a dramatic war elephant tactics charge. Ptolemy’s smaller African bush elephants panicked against Antiochus’s larger Indian elephants, disrupting the Ptolemaic left wing and allowing Antiochus’s cavalry to rout Ptolemy’s cavalry. However, Ptolemy repositioned to the center, rallying his phalanx. On the Ptolemaic right, the cavalry, bolstered by the dune-protected terrain, held firm against the Seleucid left, preventing encirclement.

The central phalanx clash proved decisive. The Ptolemaic army’s native Egyptian phalangites, trained rigorously by Sosibius, outperformed expectations, breaking the Seleucid phalanx. Dust clouds obscured Antiochus’s view as his center collapsed, and his pursuit of Ptolemy’s left wing left him disconnected. Unable to regroup, most Seleucid troops fled to Raphia, and Antiochus retreated to Gaza. The battle tactics of leveraging terrain and phalanx discipline secured Ptolemy’s victory.

Aftermath

Following the battle, Antiochus requested a truce to bury his dead, which Ptolemy granted. The Ptolemaic Kingdom retained Coele-Syria, and Ptolemy returned to Alexandria in triumph. The Raphia Decree, inscribed in Greek, hieroglyphic, and demotic Egyptian, celebrated the victory, marking Ptolemy as a pharaoh in Egyptian tradition. However, the empowerment of native Egyptians led to the Egyptian Revolt (207–186 BC), weakening the kingdom.

Casualties

According to Polybius, the Seleucid Empire suffered significant losses in the Battle of Raphia: approximately 10,000 infantry, 300 cavalry, and 5 elephants killed, with 4,000 prisoners. The Ptolemaic Kingdom lost 1,500 infantry, 700 cavalry, and 16 elephants, with most surviving elephants captured by the Seleucids. The disparity reflects the effectiveness of Ptolemy’s phalanx and the chaotic Seleucid rout, where most casualties occurred during the flight. The relatively low Ptolemaic losses highlight the success of their ancient battle formations and Hellenistic warfare tactics.

Who Won the Fourth Syrian War?

Ptolemy IV Philopator and the Ptolemaic Kingdom won the Fourth Syrian War, securing Coele-Syria and Phoenicia through their victory at the Battle of Raphia on June 22, 217 BC. The triumph halted Antiochus III the Great’s campaign to reclaim the region, reaffirming Ptolemaic dominance in the Mediterranean power struggles. However, the victory was short-lived; in 200 BC, Antiochus defeated Ptolemy V Epiphanes at the Battle of Panium, seizing Coele-Syria permanently. The Fourth Syrian War’s outcome strengthened Ptolemy IV’s rule temporarily but sowed seeds of internal unrest due to the mobilization of native Egyptians.

Conclusion

The Fourth Syrian War (219–217 BC), culminating in the Battle of Raphia on June 22, 217 BC, was a defining moment in Hellenistic conflicts, showcasing the Ptolemaic-Seleucid rivalry over Coele-Syria. Driven by Antiochus III’s ambitions and Ptolemaic vulnerabilities, the war featured ancient warfare at its peak, with war elephant tactics and ancient military strategy shaping the outcome at Raphia, near Gaza.

Ptolemy IV Philopator’s victory, driven by his innovative use of native Egyptian phalangites, secured Coele-Syria but sparked future revolts. With 10,000 Seleucid and 1,500 Ptolemaic casualties, the battle underscored the intensity of Hellenistic warfare. For historians, the Fourth Syrian War illuminates the strategic, political, and cultural dynamics of Hellenistic kingdoms, cementing its place in Syrian campaign history and Mediterranean history.

Sources:

- Polybius

- The Histories

- Book 5

- Bar-Kochva

- The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns

- Grainger

- The Seleukid Empire of Antiochus III (223–187 BC)

- Bevan

- A History of Egypt Under the Ptolemaic Dynasty