The onna-bugeisha, or female samurai, were noblewomen of Japan’s feudal era who defied traditional gender roles to become skilled warriors, fighting alongside male samurai to defend their clans and honor. Trained in martial arts and wielding weapons like the naginata and kaiken, these women left a profound mark on Japanese history through their courage and leadership. This article explores the lives and legacies of seven prominent onna-bugeisha—Akai Teruko, Ōhōri Tsuruhime, Tachibana Ginchiyo, Yuki no Kata, Hōjō Masako, Hangaku Gozen, and Tomoe Gozen—whose stories illuminate their enduring impact.

Akai Teruko: The Resilient Warrior of the Sengoku Period

Akai Teruko (1514–1590), known as “The Strongest Woman in the Warring States Period,” was a formidable onna-bugeisha during Japan’s chaotic Sengoku period (1467–1615). Born into a samurai family, she was trained in the naginata and sword, excelling in both. Teruko’s most notable contribution came during the Siege of Odawara (1590), where she fiercely defended the Hōjō clan’s stronghold against Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s forces. Her tenacity earned her legendary status, and even after the Hōjō’s surrender, she allied with Hideyoshi to attack Matsuida Castle, demonstrating strategic adaptability.

Teruko fought into her 70s, a rare feat that underscored her endurance. Historical chronicles, such as those from the Hōjō clan, praise her leadership and ability to rally troops. Her legacy as a symbol of resilience endures in Sengoku-era narratives, inspiring modern depictions of female warriors in Japanese culture.

Ōhōri Tsuruhime: The Divine Warrior Priestess

Ōhōri Tsuruhime (1526–1543), dubbed Japan’s “Joan of Arc,” was a Shinto priestess and warrior from Ōmishima Island. As the daughter of Ōhōri Yasumochi, chief priest of the Ōyamazumi Shrine, she trained in martial arts to protect her island from the Ōuchi clan. After losing her father and brothers in 1541, 15-year-old Tsuruhime assumed leadership, leading a counterattack that repelled invaders into the sea.

Her most famous exploit was sneaking aboard an Ōuchi ship and defeating their general, Ohara Takakoto, in a duel, securing a decisive victory. Proclaiming herself “Myojin of Mishima,” a divine warrior, she earned reverence among samurai pilgrims. Tragically, at 17, believing her fiancé had died, she drowned herself. Tsuruhime’s legacy lives on in Ōmishima’s festivals and folklore, celebrating her divine courage.

Tachibana Ginchiyo: The Fierce Female Daimyo

Tachibana Ginchiyo (1569–1602) was a rare female daimyo, leading the Tachibana clan in Kyushu from age 16 after her father’s death. Trained in the naginata, Ginchiyo was known for her fierce demeanor, intimidating even veteran samurai. She mandated martial arts training for all women in her castle, creating a formidable female guard.

During the Kyushu Campaign (1586), Ginchiyo led her troops alongside her husband, Tachibana Muneshige, against Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s forces, earning respect for her tactical acumen. In the Siege of Yanagawa (1600), during the Sekigahara Campaign, she organized a resistance of nuns, showcasing her innovative leadership. Her efforts preserved the Tachibana clan’s independence, and she is celebrated in Yanagawa’s festivals as a symbol of female strength.

Yuki no Kata: The Defender of Anotsu Castle

Yuki no Kata (1570–1600) was a lesser-known but valiant onna-bugeisha of the Sengoku period, renowned for her defense of Anotsu Castle during the Sekigahara Campaign (1600). Married to Katō Yoshiaki, a daimyo allied with Tokugawa Ieyasu, Yuki no Kata took charge of the castle’s defense when it was besieged by Ishida Mitsunari’s forces. Trained in the naginata and sword, she led a small garrison, holding the castle for weeks against overwhelming odds until reinforcements arrived.

Her strategic leadership and martial prowess ensured the castle’s survival, bolstering Tokugawa’s campaign. Though historical records are sparse, local accounts and temple memorials in Mie Prefecture honor her bravery. Yuki no Kata’s story, often overshadowed by male commanders, highlights the critical role of onna-bugeisha in Japan’s feudal wars.

Hōjō Masako: The Nun-Shogun

Hōjō Masako (1157–1225), known as the “nun-shogun,” was a political powerhouse during the Kamakura period (1185–1333). As the wife of Minamoto no Yoritomo, the first Kamakura shogun, and daughter of Hōjō Tokimasa, Masako wielded immense influence. While not a battlefield warrior like others, her role as an onna-bugeisha lay in her strategic governance after Yoritomo’s death in 1199. As a Buddhist nun, she ruled as regent for her sons, Minamoto no Yoriie and Sanetomo, effectively controlling the shogunate.

During the Genpei War (1180–1185), Masako supported the Minamoto’s victory over the Taira, securing alliances and resources. Her “cloistered rule” established laws granting women equal inheritance rights, elevating their status. Masako’s political legacy, chronicled in The Tale of the Heike, underscores her unique role as an onna-bugeisha in shaping Japan’s first shogunate.

Hangaku Gozen: The Archer of Torisaka

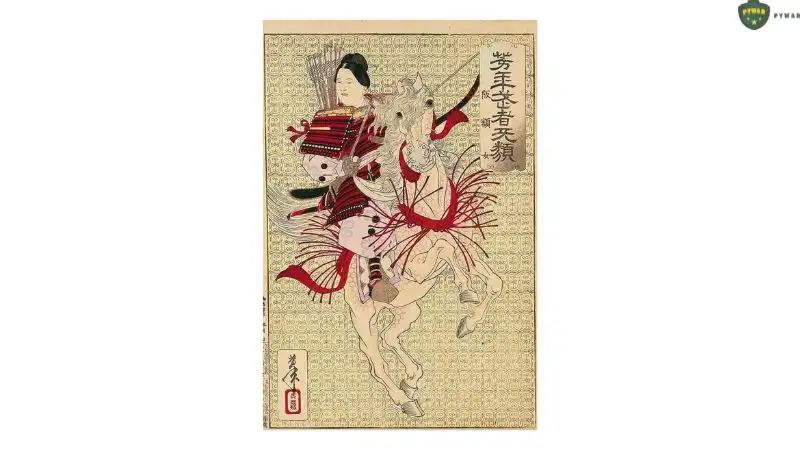

Hangaku Gozen (fl. late 12th–early 13th century) was a Taira clan warrior during the transition from the Heian to Kamakura periods. Allied with her uncle, Jo Nagamochi, she defended Torisaka Castle during the Kennin Rebellion (1201) against the Kamakura shogunate. From the castle’s tower, Hangaku’s archery skills were legendary, felling enemies with precise shots to vital areas.

Despite a three-month defense, she was wounded in the thigh by an arrow and captured. Presented to Shogun Minamoto no Yoriie, her bravery and beauty won her a marriage to Asari Yoshito, a shogunate retainer. Her fate afterward is unclear, but her stand at Torisaka, depicted in Yoshitoshi’s ukiyo-e, made her a symbol of Taira resistance and female martial valor.

Tomoe Gozen: The Iconic Warrior

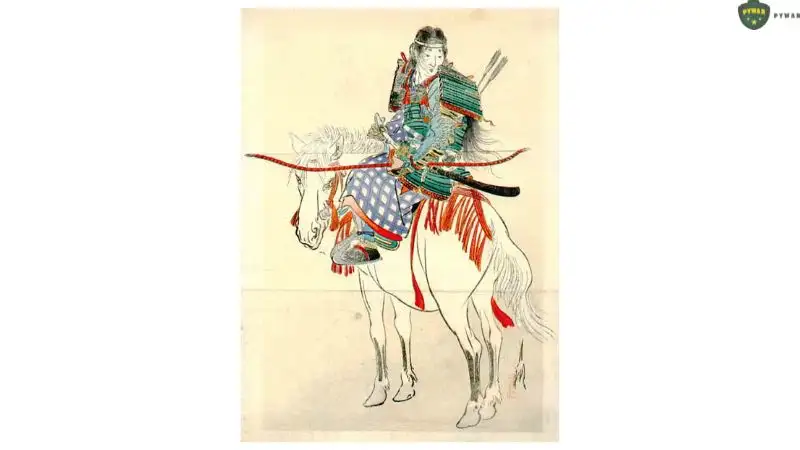

Tomoe Gozen (1157–1247) is the most celebrated onna-bugeisha, immortalized in The Tale of the Heike for her role in the Genpei War (1180–1185). Serving Minamoto no Yoshinaka, she was described as “a warrior worth a thousand,” excelling with the tachi, yumi (longbow), and on horseback. At the Battle of Awazu (1184), she led 300 samurai against 2,000 Taira warriors, beheading Honda no Morishige and surviving as one of five.

Her striking appearance—described as having “white skin, long hair, and charming features”—and martial prowess made her a legend. While some debate her historicity, her influence on naginata schools and works like the Noh play Tomoe is profound. Her fate varies in accounts: some say she became a nun, others that she drowned herself with Yoshinaka’s head. Tomoe’s legacy endures in NHK’s Yoshitsune (2005) and modern media.

Historical Context and Significance

The onna-bugeisha emerged during the Heian period (794–1185), when noblewomen of the bushi class were trained to defend their households during wartime. Their roles expanded in the Sengoku period, with figures like Akai Teruko and Tachibana Ginchiyo leading offensive campaigns. The naginata, with its long reach, was ideal for their stature, complemented by archery and tantojutsu. Women like Ōhōri Tsuruhime blended martial and spiritual roles, while Hōjō Masako wielded political power.

Key conflicts, such as the Genpei War and Sekigahara Campaign, showcased their contributions. Archaeological evidence, like female remains at Senbon Matsubaru (1580), suggests women comprised up to 30% of some battlefields. The Edo period (1603–1868) saw their decline under Neo-Confucian ideals, and the Meiji Restoration (1868) ended the samurai class, fading their martial roles.

Conclusion

The onna-bugeisha—Akai Teruko, Ōhōri Tsuruhime, Tachibana Ginchiyo, Yuki no Kata, Hōjō Masako, Hangaku Gozen, and Tomoe Gozen—embodied courage, skill, and leadership in Japan’s feudal era. From Teruko’s battlefield tenacity to Masako’s political mastery, they defied gender norms to shape history. Their legacy, preserved in festivals, literature, and media like NHK’s Yae no Sakura, continues to inspire, highlighting the enduring strength and agency of Japan’s female warriors in global historical narratives.