The Battle of Kettle Hill, fought on July 1, 1898, stands as a defining moment in the Spanish-American War, showcasing the bravery and determination of American forces, including the famed Rough Riders led by Theodore Roosevelt. This engagement, part of the larger Battle of San Juan Heights, was instrumental in securing American control over Santiago de Cuba, paving the way for the eventual surrender of Spanish forces in Cuba. This article delves into the details of the battle, exploring its time and date, location, causes, course, casualties, and outcome, providing a comprehensive overview for history enthusiasts and researchers alike.

Time and Date of the Battle

The Battle of Kettle Hill took place on July 1, 1898, during the Spanish-American War. The assault began in the early afternoon, following intense preparations and earlier engagements at El Caney. This date marked a critical point in the U.S. campaign to capture Santiago de Cuba, a key Spanish stronghold on the island.

Location of the Battle

Kettle Hill, named by American troops, was one of two prominent high points along the San Juan Heights, located approximately 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) east of Santiago de Cuba, on the southern coast of the island. The hill, alongside the adjacent San Juan Hill, formed a strategic ridge overlooking the city, making it a critical target for American forces aiming to besiege Santiago. The terrain was rugged, with Kettle Hill featuring a steep incline and a Spanish blockhouse at its crest, fortified by trenches and defended by well-armed Spanish troops. The surrounding area, known as “Hell’s Pocket,” was a deadly zone where American troops faced intense enemy fire during their advance.

Causes of the Conflict

The Battle of Kettle Hill was a key engagement within the broader context of the Spanish-American War (1898), a conflict driven by a combination of American imperial ambitions, humanitarian concerns, and geopolitical tensions. Several factors contributed to the outbreak of the war and the specific focus on capturing Santiago, where Kettle Hill played a pivotal role:

- Cuban War of Independence: By 1898, Cuba was embroiled in a struggle for independence from Spanish colonial rule. Spanish efforts to suppress the rebellion were marked by brutal tactics, including the “reconcentración” policy, which forcibly relocated Cuban civilians into camps, leading to widespread suffering and death. Sensationalized reports of Spanish atrocities in American newspapers, often exaggerated by “yellow journalism,” fueled public outrage in the United States, rallying support for intervention.

- Sinking of the USS Maine: The explosion of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898, killing 266 American sailors, became a rallying cry for war. Although the cause of the explosion remains disputed, American media and politicians attributed it to Spanish sabotage, intensifying calls for military action.

- American Imperial Ambitions: The late 19th century saw the United States seeking to expand its influence as a global power. Capturing Cuba, a strategically located Caribbean island, offered economic and military advantages, including control over key trade routes and naval bases.

- Strategic Importance of Santiago: Santiago de Cuba was a major Spanish stronghold and the site of a significant Spanish fleet. Capturing the city was essential for the U.S. to disrupt Spanish control over Cuba. The San Juan Heights, including Kettle Hill, were the last major obstacles to encircling Santiago, making their capture a strategic necessity.

These factors converged to create a climate where American military intervention in Cuba became inevitable, with Kettle Hill emerging as a focal point in the campaign to secure Santiago.

Course of the Battle

The Battle of Kettle Hill was part of a coordinated American assault on the San Juan Heights, which included both Kettle Hill and the adjacent San Juan Hill. The U.S. Army Fifth Corps, under the command of General William Rufus Shafter, faced a Spanish force led by General Arsenio Linares y Pombo. The American forces, numbering around 8,000 troops, significantly outnumbered the approximately 750 Spanish defenders entrenched on the heights. However, the Spanish were well-equipped with Model 1893 Mauser rifles, which used smokeless powder and stripper clips for rapid reloading, giving them a significant firepower advantage. The battle unfolded as follows:

Morning Preparations and Delays

On the morning of July 1, 1898, General Shafter’s plan called for a two-pronged assault. The 2nd Division, under Brigadier General Henry W. Lawton, was tasked with capturing El Caney, a fortified village 3.75 miles east of Santiago, before joining the main assault on San Juan Heights. Meanwhile, the 1st Infantry Division, led by Brigadier General Jacob Kent, and the Dismounted Cavalry Division, under Brigadier General Samuel Sumner, prepared to attack the heights, including Kettle Hill.

The plan quickly encountered difficulties. The march to attack positions was delayed by narrow, crowded trails and intense Spanish fire. The attack on El Caney, expected to be swift, turned into a prolonged nine-hour struggle due to fierce Spanish resistance, delaying Lawton’s division from joining the assault on the heights. By noon, the American forces were still organizing, with troops enduring heavy Spanish fire from the entrenched positions atop Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill.

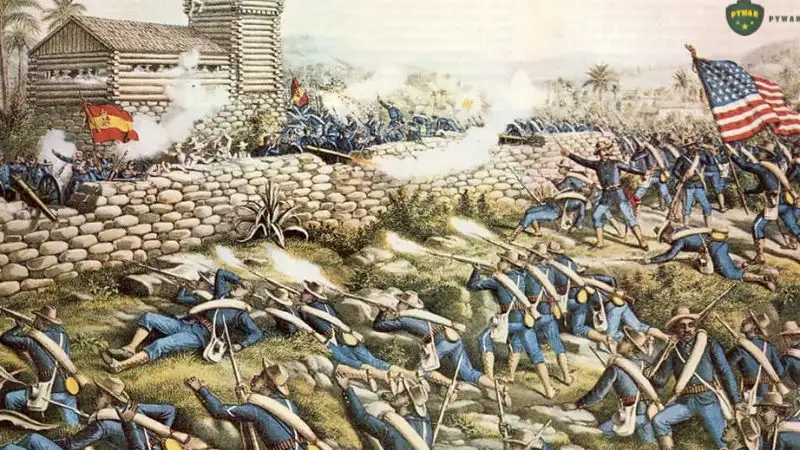

The Assault on Kettle Hill

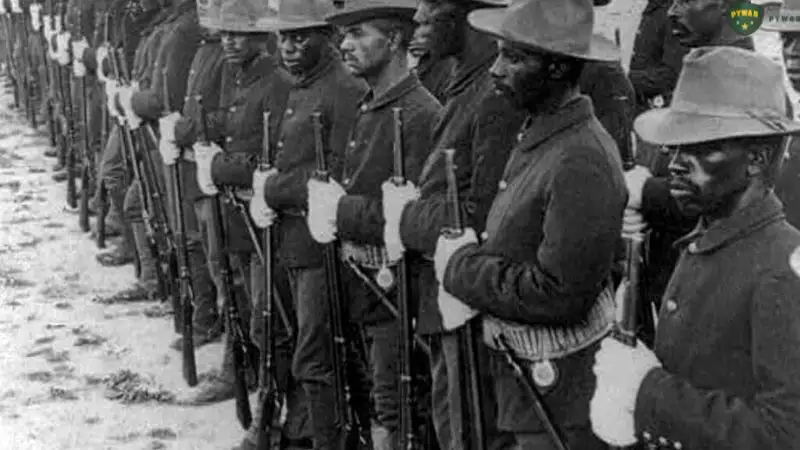

At approximately 1:00 PM, with the El Caney engagement still unresolved, Shafter’s aide authorized the attack on San Juan Heights. The Dismounted Cavalry Division, including the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry (Rough Riders) under Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, the 3rd Cavalry, and the 9th and 10th Cavalry (Buffalo Soldiers), targeted Kettle Hill. The Rough Riders, a diverse volunteer regiment composed of cowboys, Native Americans, and college athletes, had been forced to leave their horses behind due to transportation issues, fighting as dismounted cavalry.

The assault began under intense Spanish fire from the blockhouse and trenches atop Kettle Hill. American troops faced a grueling advance through “Hell’s Pocket,” a low-lying area where they were exposed to accurate Mauser fire. The Gatling Gun Detachment, commanded by Lieutenant John H. Parker, played a critical role in supporting the assault. Positioned at the base of the hill, the Gatling guns unleashed a staggering 18,000 rounds in eight and a half minutes, delivering over 700 rounds per minute. This barrage disrupted Spanish defenses, suppressing their fire and allowing American troops to advance.

Leading the charge, Theodore Roosevelt, on horseback, inspired his Rough Riders to storm the hill. The 9th and 10th Cavalry, alongside the 24th and 25th Infantry (Buffalo Soldiers), also played a pivotal role, charging up the steep incline under heavy fire. Despite suffering significant casualties, the American forces reached the crest, engaging in close-quarters combat. By mid-afternoon, the Rough Riders, supported by the Buffalo Soldiers and other units, captured the Spanish blockhouse, forcing the defenders to retreat.

Support for San Juan Hill

While Kettle Hill was being secured, the 1st Infantry Division assaulted San Juan Hill, facing similar challenges from entrenched Spanish positions. The capture of Kettle Hill allowed American Gatling guns to provide supporting fire against Spanish troops on San Juan Hill, repulsing a Spanish counterattack late in the afternoon. By the end of the day, both hills were under American control, giving U.S. forces a commanding position overlooking Santiago.

Nighttime Consolidation

After capturing Kettle Hill, American forces faced the threat of a Spanish counterattack. General Shafter initially ordered a withdrawal, fearing the position was vulnerable to artillery fire from Santiago. However, General Joseph Wheeler, supported by Generals Kent and Sumner, convinced Shafter to hold the line. Overnight, American troops fortified their positions with breastworks, preparing for potential Spanish assaults. Reinforcements arrived, strengthening the American hold on the heights.

Casualties

The Battle of Kettle Hill was a costly engagement for both sides, reflecting the intensity of the fighting and the challenging terrain. American casualties on Kettle Hill alone included 35 dead and numerous wounded, with the broader assault on San Juan Heights resulting in 205 killed and 1,180 wounded across all units involved. Notable losses included Lieutenant Jules G. Ord, who was mortally wounded near the crest of San Juan Hill, and General Hamilton S. Hawkins, who was wounded during the assault.

Spanish casualties were also significant, with 58 killed on Kettle Hill and a total of 215 killed and 376 wounded across the San Juan Heights. The Spanish defenders, despite their numerical disadvantage, inflicted heavy losses due to their superior weaponry and fortified positions. The high casualty rates underscored the ferocity of the battle and the determination of both sides.

Who Won the Battle of Kettle Hill?

The United States emerged victorious in the Battle of Kettle Hill. The capture of the hill, combined with the simultaneous assault on San Juan Hill, secured the San Juan Heights, giving American forces a strategic vantage point over Santiago. This victory was a turning point in the campaign, enabling the U.S. to initiate a siege of the city on July 2. The destruction of the Spanish fleet on July 3 and the subsequent surrender of Santiago on July 17 effectively ended Spanish control over Cuba, marking a decisive American triumph in the war.

The victory at Kettle Hill was widely celebrated in the American press, with Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders receiving significant attention. However, the contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers—the 9th and 10th Cavalry and 24th and 25th Infantry—were initially underreported, despite their critical role in the assault. Over time, their bravery, including that of Quarter Master Sergeant Edward L. Baker, Jr., who received the Medal of Honor, has been increasingly recognized.

Conclusion

The Battle of Kettle Hill, fought on July 1, 1898, was a pivotal moment in the Spanish-American War, showcasing the courage and coordination of American forces in overcoming a well-entrenched Spanish defense. Driven by tensions over Spanish rule in Cuba, the sinking of the USS Maine, and American imperial ambitions, the battle was a critical step toward capturing Santiago and securing U.S. victory in the war.

The intense fighting, supported by innovative use of Gatling guns and the leadership of figures like Theodore Roosevelt, resulted in heavy casualties but ultimately a decisive American triumph. The legacy of Kettle Hill endures as a testament to the bravery of all who fought, including the often-overlooked contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers, and its role in shaping the United States’ emergence as a global power.