The Domino Theory was a Cold War policy asserting that if one nation succumbed to communism, nearby countries would quickly follow, akin to dominoes falling one after another. In Southeast Asia, the United States government used this now-discredited theory to justify its intervention in the Vietnam War and to support a non-communist regime in South Vietnam.

However, history has shown that the U.S. failure to prevent a communist victory in Vietnam did not trigger the widespread domino effect predicted by the theory’s proponents. Apart from Laos and Cambodia, communism did not spread across Southeast Asia as initially feared. In this article, Pywar will explain what the Domino Theory entails and how it influenced the Vietnam War.

North and South Vietnam

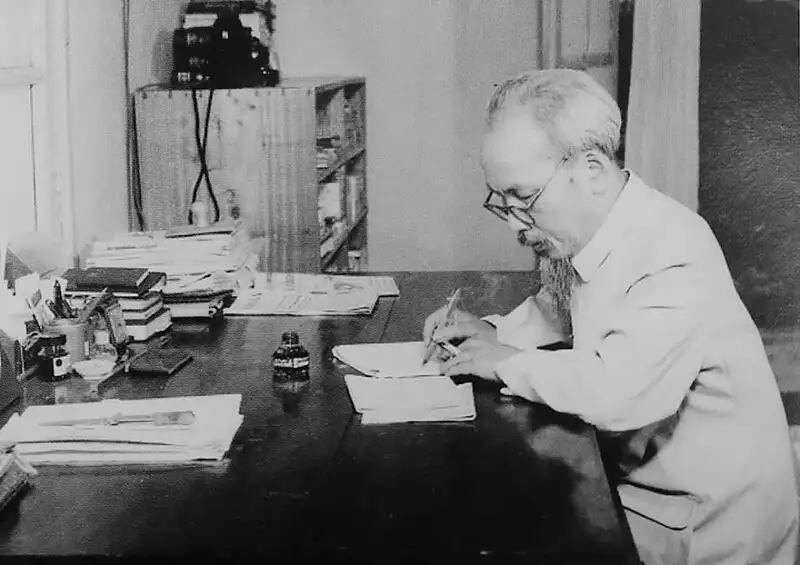

In September 1945, nationalist leader Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s independence from France, initiating a conflict between the communist-led Viet Minh government in Hanoi (North Vietnam) and the French-backed regime in Saigon (South Vietnam).

Under President Harry Truman, the U.S. government secretly provided military and financial aid to France, reasoning that a communist victory in Indochina would spur the spread of communism throughout Southeast Asia. Using similar logic, Truman also supported Greece and Turkey in the late 1940s to curb communist expansion in Europe and the Middle East.

- U.S. soldiers in Vietnam amid the context of the Domino Theory. (Source: Collected)

What Is the Domino Theory?

By 1950, U.S. foreign policy planners were firmly convinced that the fall of Indochina to communism would rapidly lead to the collapse of other Southeast Asian nations. The National Security Council referenced this theory in a 1952 report on Indochina, and in April 1954, during the decisive battle between the Viet Minh and French forces at Dien Bien Phu, President Dwight D. Eisenhower articulated the “domino” principle clearly:

“You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly,” Eisenhower stated. “So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.”

In Eisenhower’s view, the loss of Vietnam to communism would lead to similar communist victories in neighboring Southeast Asian countries (including Laos, Cambodia, and Thailand) and beyond (India, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, and even Australia and New Zealand). “The possible consequences of the loss [of Indochina],” Eisenhower emphasized, “are just incalculable to the free world.”

Following Eisenhower’s speech, the term “Domino Theory” began to be used as a shorthand expression for the strategic importance of South Vietnam to the United States and the need to contain the global spread of communism.

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower explaining the Domino Theory. (Source: Collected) (Source: Collected)

The Deepening U.S. Involvement in Vietnam

After the Geneva Conference ended the war between France and the Viet Minh and partitioned Vietnam at the 17th parallel, the United States took the lead in forming the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO)—a loose alliance of nations committed to responding to “security threats” in the region.

President John F. Kennedy, Eisenhower’s successor, increased U.S. resource support for the Ngo Dinh Diem government in South Vietnam and non-communist forces in the Laotian civil war in 1961-1962. However, by 1963, as domestic opposition to Diem’s regime grew, Kennedy began withdrawing support for Diem while publicly reaffirming his belief in the Domino Theory and the importance of containing communism in Southeast Asia.

Three weeks after Diem was assassinated in a military coup in early November 1963, President Kennedy was also assassinated in Dallas. His successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, continued to invoke the Domino Theory to justify escalating the U.S. military presence in Vietnam, growing from a few thousand troops to over 500,000 within the next five years.

- U.S. troops during the military escalation in Vietnam. (Source: Collected) (Source: Collected)

Nations Are Not Dominoes

The Domino Theory has since been largely discredited, as it failed to accurately reflect the nature of North Vietnam’s and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam’s (Viet Cong) struggle during the Vietnam War.

The assumption that Ho Chi Minh was a pawn of communist powers like the Soviet Union and China caused U.S. policymakers to overlook his true objective—and that of his supporters—which was to secure Vietnam’s independence, not to expand communism.

Ultimately, despite the U.S. failure to prevent communist domination and North Vietnamese forces entering Saigon in 1975, communism did not spread throughout Southeast Asia. Apart from Laos and Cambodia, the region’s nations remained outside communist control.

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower signing a document related to the Domino Theory. (Source: Collected) (Source: Collected)

Conclusion

Through this article on the Domino Theory, Pywar hopes you’ve gained a clearer understanding of this Cold War strategic policy. The United States used the theory to justify its intervention in Vietnam and Southeast Asia, driven by fears of communism’s spread. However, history has shown that Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh aimed for national independence, not communist expansion. Despite the U.S. failure to stop North Vietnam, communism did not engulf Southeast Asia as feared.

Translated by: Le Tuan

Source: history.com – Domino Theory