The Vietnam War is not only a tragic chapter in the history of both nations but also a period marked by the deep involvement of five U.S. presidents. From Harry Truman’s initial steps, Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Domino Theory, to Lyndon B. Johnson’s escalation policies, each president left a distinct mark on the war. Join Pywar as we uncover the truth about the five U.S. presidents during the Vietnam War.

Facts About the 5 U.S. Presidents During the Vietnam War

President Harry Truman

U.S. State Department officials in Asia warned President Harry Truman, who took office in 1945 after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death, that France’s reoccupation of Vietnam would lead to “bloodshed and unrest.” However, unlike his predecessor’s anti-colonial stance, Truman ultimately agreed to restore France’s pre-war empire, hoping it would strengthen France’s economy and national pride.

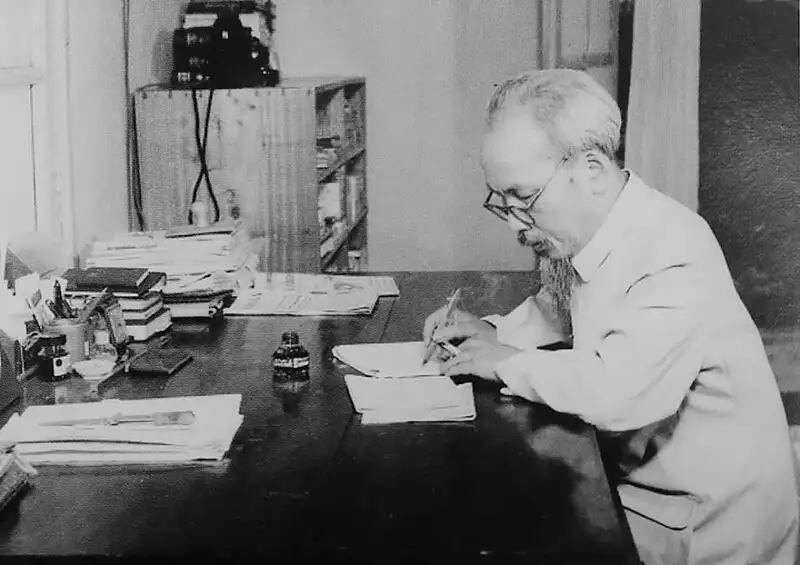

As French forces returned to Vietnam—while World War II’s wounds were still fresh—conflict erupted with Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh. Initially, the U.S. maintained an official neutral stance, avoiding any association with Ho Chi Minh. But in 1947, Truman declared that U.S. foreign policy would support any nation threatened by communism.

The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, combined with aid from China and the Soviet Union to the Viet Minh, prompted Truman to view Vietnam through a Cold War lens. Fearing Vietnam would also fall to communism, he sent transport planes, Jeeps, and 35 military advisors as part of a multimillion-dollar aid package.

From this point, U.S. involvement deepened. By the end of Truman’s term, the U.S. was funding over a third of France’s war costs—a figure that soon rose to about 80%.

- Harry Truman – The 33rd President of the United States, who initiated U.S. involvement in Vietnam after World War II. (Source: Collected)

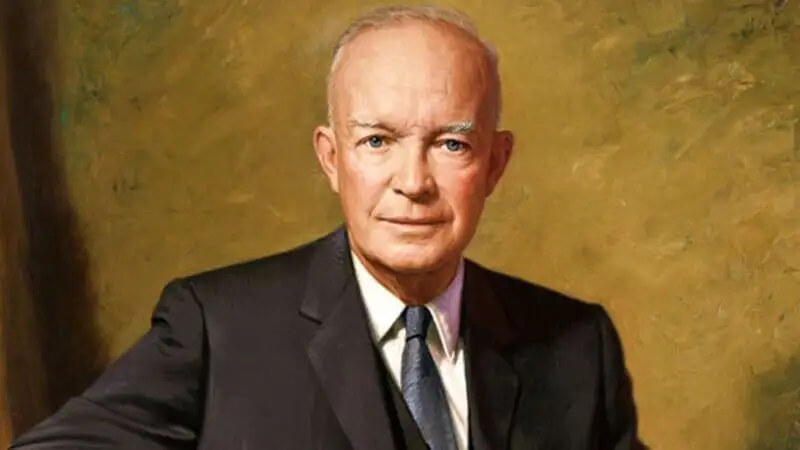

President Dwight D. Eisenhower

In 1954, France suffered a catastrophic defeat at Dien Bien Phu, ending its colonial rule in Vietnam. Some U.S. officials proposed airstrikes, including the potential use of nuclear weapons, to salvage France’s position. However, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Truman’s successor, refused, unwilling to drag the U.S. into another major conflict so soon after the Korean War.

“I am convinced that no military victory is possible in such a theater,” the president wrote in his diary.

Yet, believing in the “Domino Theory”—that if one nation fell to communism, its neighbors would follow—Eisenhower rejected a complete withdrawal from Vietnam.

The country was split into two, with Ho Chi Minh controlling the North and Ngo Dinh Diem, a Western-aligned leader, ruling the South. Elections to unify Vietnam were planned, but Diem, with U.S. backing, withdrew, fearing Ho’s victory.

Though Diem proved corrupt and authoritarian, Eisenhower called him “the greatest of statesmen” and “an example to those who hate tyranny and love liberty.” More crucially, Eisenhower supported Diem with funds and arms, providing nearly $2 billion in aid from 1955 to 1960 and increasing military advisors to about 1,000.

By the time Eisenhower left office, open fighting had broken out between Diem’s forces and the Viet Cong, communist insurgents in the South backed by the North. Both sides employed brutal tactics, including torture and political assassinations. The Vietnam War had truly begun, and the U.S. was being drawn into the fray.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower – The 34th President of the United States, who implemented the “Domino Theory” and strongly supported South Vietnam. (Source: Collected)

President John F. Kennedy

In 1951, as a congressman visiting Vietnam, John F. Kennedy publicly criticized U.S. support for France, arguing that “denying innate national aspirations would inevitably lead to failure.” Three years later, he accurately predicted: “Frankly, I believe no amount of American military aid… can defeat an enemy that is everywhere and nowhere.”

Yet, Kennedy’s views shifted by the 1960 presidential campaign, partly due to fears of appearing soft on communism. Once in the White House, he supplied South Vietnam with fighter jets, helicopters, armored vehicles, river patrol boats, and other war tools. He also authorized the use of napalm and herbicides like Agent Orange.

Under Kennedy, the number of U.S. military advisors surged from about 800 to 16,000, some engaging in covert combat operations. Initially supportive of Ngo Dinh Diem, Kennedy later approved a 1963 coup that led to Diem’s death just weeks before his own assassination. Near the end of his life, Kennedy hinted to aides he might withdraw from Vietnam after re-election, though it’s unclear if he would have followed through.

- John F. Kennedy – The 35th President of the United States, who bolstered military aid and advisors to South Vietnam. (Source: Collected)

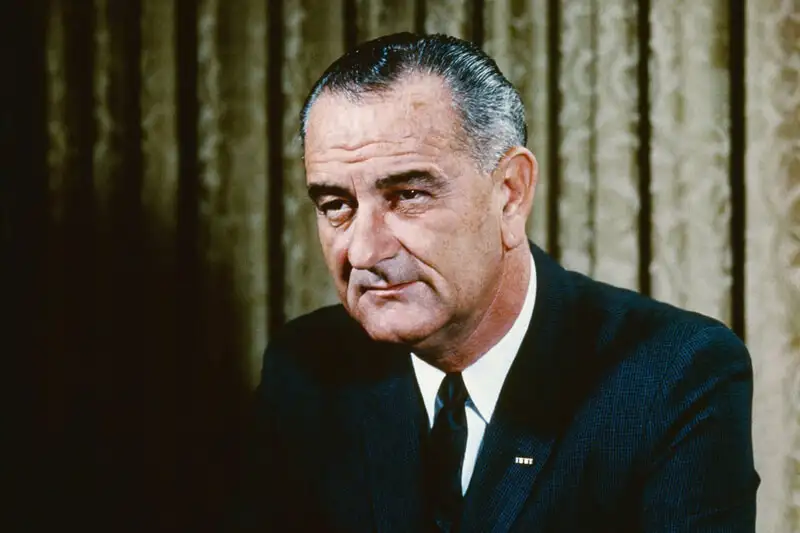

President Lyndon B. Johnson

When John F. Kennedy was assassinated, U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War remained relatively limited. That changed in August 1964, when the Gulf of Tonkin Incident led Congress to grant sweeping war powers to newly inaugurated President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Seeing South Vietnam’s government and military on the brink of collapse, Johnson deployed the first U.S. combat troops in early 1965. He also approved a massive bombing campaign, “Operation Rolling Thunder,” which persisted for years.

Draft calls soared—sparking widespread draft resistance. By 1967, about 500,000 U.S. troops were in Vietnam. That same year, large-scale anti-war protests erupted across U.S. cities.

U.S. officials repeatedly claimed victory was near. But as the Pentagon Papers later revealed, these claims were false. In reality, the conflict was hopelessly bogged down. The Vietnam War deeply divided American society, and Johnson’s legacy became so tied to the war effort that he chose not to run for re-election in 1968.

- Lyndon B. Johnson – The 36th President of the United States, who dramatically escalated U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. (Source: Collected)

President Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon campaigned for president promising to end the Vietnam War. However, it was later discovered he secretly sabotaged peace talks to boost his election chances.

As president, Nixon gradually withdrew U.S. troops under his “Vietnamization” policy. Yet, he escalated the conflict in other ways, approving secret bombings of Cambodia in 1969, sending troops into Cambodia in 1970, and backing a similar invasion of Laos in 1971. These aimed to disrupt North Vietnam’s supply lines and destroy Viet Cong bases but were largely ineffective.

Nixon also ordered the war’s most intense bombing campaign, dropping about 36,000 tons of bombs on North Vietnamese cities in late 1972.

In January 1973, as the Watergate scandal emerged, Nixon announced the end of direct U.S. involvement in Vietnam, claiming “peace with honor” had been achieved. In reality, fighting continued until 1975, when North Vietnamese forces captured Saigon, South Vietnam’s capital, unifying the country under communist rule.

- Richard Nixon – The 37th President of the United States, who both withdrew troops and escalated the conflict in Vietnam (Source: Collected)

Conclusion

The Vietnam War was a complex, protracted conflict shaped by these five presidents. From Truman’s initial aid to Nixon’s final exit, their policies cost over 58,000 American and roughly 3 million Vietnamese lives, leaving enduring lessons on politics, warfare, and humanity.

Translated by: Le Tuan

Source: history.com – How the Vietnam War Ratcheted Up Under 5 US Presidents